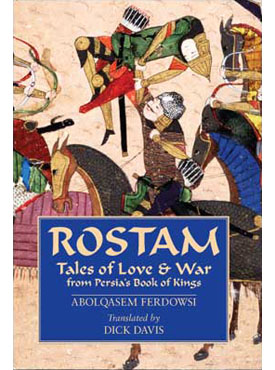

About the Book

Rostam is Iran’s greatest mythological hero, a Persian Hercules, magnificent in strength and courage. As re-counted in the tenth-century Book of Kings (Shahnameh) by the poet Ferdowsi, he was an indomitable force in ancient Persia for five hundred years, undergoing many trials of combat, cunning, and endurance. Although Rostam served a series of often-fickle kings, he was always his own man, committed to the greater good of Iran. His adventures are some of the best loved of all Persian narratives and remain deeply resonant in Iranian culture. Rostam: Tales of Love & War from Persia’s Book of Kings begins with the birth of Rostam’s father Zal and ends with Rostam’s death. The tales tell of the love between Zal and Rostam’s mother, the Kaboli princess Rudabeh; of Rostam’s miraculous birth, aided by the magical bird Simorgh; of Rostam’s youth and the selection of his trusty horse Rakhsh; of his affair with Princess Tahmineh, the birth of their son Sohrab, and, after Sohrab grows into a mighty warrior himself, the tragic confrontation between father and son. The tales conclude with Rostam’s war against demons, his seven trials, his rescue of Prince Bizhan, and finally his battle, both intellectual and physical, with the ambitious and religiously driven prince Esfandyar.

Reviews

Selected as one of the top 5 fiction books of 2006

Grand . . . To imagine an equivalent to this violent and beautiful work, think of an amalgam of Homer’s Iliad and the ferocious Old Testament book of Judges. . . . Thanks to Davis’s magnificent translation, Ferdowsi and the Shahnameh live again in English. This marvelous translation of an ancient Persian classic brings these stories alive for a new audience.

–Washington Post Book World, Michael Dirda

The Shahnameh has much in common with the blood-soaked epics of Homer and with Paradise Lost and The Divine Comedy. . . . The poem is, in a sense, Iran’s national scripture, and Ferdowsi Iran’s national poet. . . . Davis brings to his translation a nuanced awareness of Ferdowsi’s subtle rhythms and cadences. . . . His Shahnameh is rendered in an exquisite blend of poetry and prose.

–The New York Times Book Review, Reza Aslan

It takes Dick Davis’s delightful and animated translation of Persia’s classic 623 pages to get around to banning wine-drinking, a prohibition ended by royal decree two pages later, with 257 pages of music, seduction, and polo matches left to go. All this action, myth, and history fairly fly off the page, for Davis renders Ferdowsi’s 50,000 sesquipedalian lines of poetry as a prose narrative that here and there erupts into sonnet-sized snatches of verse. The scheme works brilliantly.… ‘That poetry which is the most difficult,” wrote Irshad Ullah Khan, “has been rendered into English … with the comparative strength of the inspirational truth and elegance of the Persian. His work shall not die. It is hard to vouch for any volume’s immortality, but this ranks among the best Persian translations of the last thousand years.”

–The New Criterion, Russel Seitz

Davis’s wonderful translation will show Western readers why Ferdowsi’s masterpiece is one of the most revered and most beloved classics in the Persian world.

-Khaled Hosseini, author of The Kite Runner

Excerpt

FROM THE INTRODUCTION

Rostam is the greatest hero of pre-Islamic Persian legend, and he and his exploits dominate the first half of our principal source for such material, the Shahnameh, the magnificent compendium of verse narratives concerned with pre-Islamic Iran that was written down by the poet Ferdowsi at the end of the tenth and the beginning of the eleventh centuries c.e.

As befits an ancient hero he is a larger-than-life figure: he lives for over five hundred years, he undergoes seven trials of strength, cunning, and endurance that put him in the same company as Hercules and his labors, he defeats and kills not only innumerable human enemies but also dragons and demons, he serves as the pre-eminent champion of no less than five Persian monarchs and lives through much of the reigns of two more. After his death, he is constantly evoked by those who come after him as the epitome of magnanimity, manliness, heroism, and loyalty to the Persian throne. The stories in which he figures are the best-known and most loved narratives of the Shahnameh, and are among the most famous in Persian culture.

But Rostam is not simply a paragon of heroic loyalty to the Persian throne mythologized and writ large. Something that runs throughout all the narratives in which he is involved is his insistence that he is his own man, that his service is given voluntarily and cannot be constrained, and that he is at no one’s beck and call, not even his king’s. If he is loyal it is because he chooses to be, and sometimes he chooses not to be. There is something anarchic about him, a contempt for boundaries and borders (both literal and metaphorical ones), a stubbornness and eagerness to excel, which can remind a Western reader of Shakespearian heroes like Coriolanus or Warwick (called, as Rostam is too, “the kingmaker”), an overreaching that like theirs can lead directly to tragedy. Much of the glamour of Rostam’s legend lies in the tension between this fierce independence, which places him outside of authority, and his seemingly inexhaustible (until it is in fact exhausted) service to the Persian monarchy and the country it controls. If the Shahnameh is primarily, as its name (the “book of kings”) implies, about monarchy, and so about a center of absolute or would-be absolute power, Rostam is a figure from outside of that center of power; he is one who lives, in all senses, at the edge.

We can see this “at the edge” quality clearly in his origins, which indicate his tangential relationship both to the land of Iran and to humanity in general. His parents are the Persian hero Zal and the Kaboli princess Rudabeh. When Zal is born, his father exposes him on a mountainside to die because of his white hair and mottled skin, and he is brought up by a fabulous magical bird, the Simorgh. The implication is that there is something demonic about Zal’s appearance, and indeed there is only one other figure in the Shahnameh who is described as having white hair and a mottled skin, the White Demon of Mazanderan, whom Rostam kills in single combat, and who almost kills him. Once one has registered the similarity in the descriptions of the demon’s appearance and that of Rostam’s father, it is hard not to see this struggle as an Oedipal reversal of a common motif in the Shahnameh, the death of sons through the actions of their fathers.

When Zal has returned to the human world the Simorgh remains his protector, and she is later on (through Zal as an intermediary) the protector of his son Rostam; in their ability to call on her magical aid in moments of extreme peril they are given access to magical powers. The supernatural as part of Rostam’s inheritance, again in somewhat demonic guise, is even more evident on his mother’s side: Rudabeh’s father is Mehrab, the king of Kabol, who is descended from the demon king Zahhak, from whose clutches Iran was freed by the noble king Feraydun. Zal’s king, Manuchehr, at first opposes Zal’s marriage to Rudabeh because this will mingle the demonic bloodline of Zahhak with that of the Persian heroes (and Rostam is the result of just such a mingling). In human terms then, Rostam is certainly “at the edge”: he can call on magic, he is descended from a demon on his mother’s side, and his father’s strange upbringing and appearance also bring with them an aura of the supernatural and perhaps the demonic. Rostam is a great subduer of demons, but as with another Persian hero (and king this time) Jamshid, whose authority over demons seems at times to come as much from his participation in their world as his defeat of it, there is a suggestion of “set a thief to catch a thief” about his prowess.

Geographically Rostam belongs in Sistan, his family’s appanage, granted in perpetuity by the Persian kings for their loyalty to the throne. The area may have been granted by the kings, but when Rostam is uneasy with the political goings-on at the Persian court, it is to this area that he retreats, where he is beyond the reach of the king unless he wishes to present himself of his own free will. Like Achilles, Rostam is often contumacious and moody, and Sistan is his equivalent of Achilles’s tent: it’s the place he goes to sulk, to indicate that he has washed his hands of his people’s problems.

The modern Sistan, the southeastern province of Iran, does not correspond with Zal’s and Rostam’s kingdom, which lies largely to the east of this area, in what is now the province of Helmand in Afghanistan. The river Helmand (called, in Ferdowsi’s time, the Hirmand) marks the northern border of their territory. Rostam’s land is therefore on the eastern edge of the Iranian world. His mother is from Kabol, and Rostam dies in Kabol, placing his origin and death even further to the east; indeed, in the terms of the Shahnameh placing them in India, as Kabol is seen as a part of India throughout the Shahnameh. There are other indications of a strong Indian presence in Rostam’s identity: the talismanic tiger skin he wears instead of armor, the babr-e bayan as it is called in Persian, has been traced to an Indian origin by the scholar Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh, and another eminent scholar of the Shahnameh, Mehrdad Bahar, has pointed out that some aspects of Rostam’s legend parallel and may derive from those of the Hindu god Krishna. Sistan, Kabol, India—certainly, if we take Iran as the center, Rostam hails geographically from the edge, and, significantly enough, from the eastern edge. Significantly because the lands immediately to the east of Iran are seen as the origin of magic in the Shahnameh, and this eastern aspect of his identity further ties Rostam to that supernatural and chthonic world his parentage implies.

Often Rostam’s heroism too has an “edgy,” unstraightforward quality to it. The supernatural Simorgh, on whose help he can rely, as well as the tiger skin he wears both suggest characteristics of the Trickster Hero, as he is found in many cultures. Tricksters are often associated with magic, and they have something of the shaman about them, one who is in touch with other worlds, often through an animal intermediary, and is able to call the denizens of these worlds to his and his people’s aid. Many tricksters are associated with specific animals whose skins or feathers they wear in order to draw on the animal’s characteristics for their own purposes. The animals so used are usually known for their slyness, or they are birds. Rostam is protected by the feathers of a fabulous bird, and he wears a tiger skin, and slyness is exactly the quality associated with tigers in Indian lore (e.g., in Buddhist Jataka tales: there is a distant echo of this in Kipling’s Shere Khan in The Jungle Book)..

About the Author

About the Translator

Dick Davis brings a unique array of gifts to the challenges of translating Hafez and his contemporaries. In his own right, he is a poet of great technical accomplishment and emotional depth. He is also the foremost English-speaking scholar of medieval Persian poetry now working in the West. Numerous honors testify to his talents. In the U.K., he received the Royal Society of Literature’s Heinemann Award for his second book of poems, Seeing the World, in 1981; his Selected Poems was chosen by both the Sunday Times and the Daily Telegraph as a Book of the Year in 1989; and his collection Belonging was selected as the Poetry Book of the Year by The Economist in 2003. In the U.S., A Kind of Love—the American edition of his Selected Poems—received the Ingram Merrill prize for “excellence in poetry” in 1993. He has received awards for his scholarship from the Arts Council of Great Britain, The British Institute of Persian Studies, and the Guggenheim Foundation, and he is the recipient of grants for his translations from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts. Twice, in 2000 and 2001, he received the Translation Award of the International Society for Iranian Studies, and in 2001 he received an Encyclopedia Iranica award for “services to Persian poetry.” His translation of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: the Persian Book of Kings was chosen as one of the “ten best books of 2006” by the Washington Post.

Davis read English at Cambridge, lived in Iran for eight years (he met and married his Iranian wife Afkham Darbandi there), then completed a PhD in Medieval Persian Literature at the University of Manchester. He has resided for extended periods in both Greece and Italy (his translations include works from Italian), and has taught at both the University of California and at Ohio State University, where he was for nine years Professor of Persian and Chair of the Department of Near Eastern Languages, retiring from that position in 2012. In all, he has published more than twenty books and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

Among the qualities that distinguish his poetry and scholarship are exacting technical expertise and wide cultural sympathy—an ability to enter into distant cultural milieus both intellectually and emotionally. In choosing his volume of poems Belonging as a “Book of the Year” for 2006, The Economist praised it as “a profound and beautiful collection” that gave evidence of “a commitment to an ideal of civilized life shared by many cultures.” the Times Literary Supplement has called him “our finest translator of Persian poetry.” In 2009 Mage published a book of Dick Davis’s own poems about Iran: At Home and Far From Home: Poems on Iran and Persian Culture. His book about the Shahnameh, Epic and Sedition was published by Mage in paperback in 2006. His books of translations are: Borrowed Ware: Medieval Persian Epigrams (1998), The Shahnameh (2004); The Legend of Seyavash (2004); Rostam: Tales of Love and War from Persia’s Book of Kings (2007); Vis and Ramin (2008); Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz (2012).